07 | Groundwork | The Web as a Medium: Four Observations

December 26th, 2011 by bruno boutotNote: The five posts entitled “Groundwork” were originally written in 2009. See here.

.

The relationship of the customer to the business will likely be redefined, not by social media but by a broader set of tools and new contexts for relationship. Jon Lebkowsky Thinking about the future of online marketing

Take a truck made of 10 tons of metal and plastic. Make it plunge into the sea from the end of a pier. It will sink. Launch it in the air from the top of a cliff. It will crash. That doesn’t mean that you can’t make 10 tons of metal and plastic ride the waves or fly through the air. It just means that we build our vehicles according to the characteristics of each medium. When we stop trying to drive our trucks into the ocean, we can observe the Web as a different medium.

Four observations on the Web as a communication medium:

- Proximity

- Origin

- Equality

- Memory

I call them “observations” because that’s what they are: points that appear again and again with the same effects everywhere. One way of reading McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” is to take into account all the perceptions implied by the medium and around it. These observations are perceptions implied by the medium. Perception is reality: everything happens as-if. The observations are listed in no particular order: they all exist at the same time. The consequences of each one are explored in detail in later posts. I’ll just begin by defining briefly what each word means in this context. So here they are: three of them define a physical property of communication in this medium; the fourth one took me more time to grasp.

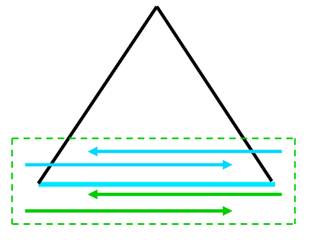

- Proximity: For a user of the Web, every page is a click away.

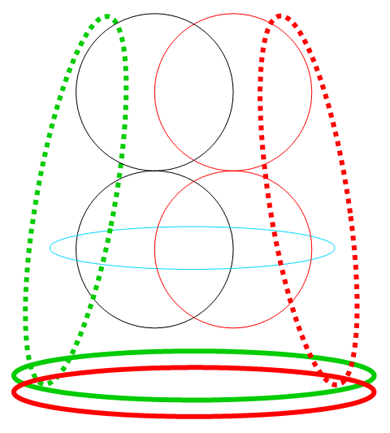

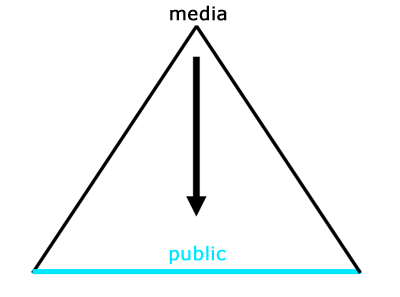

- Origin: On the Web, communication starts from the user.

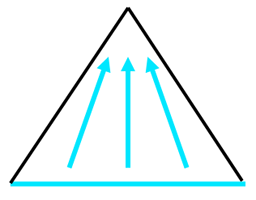

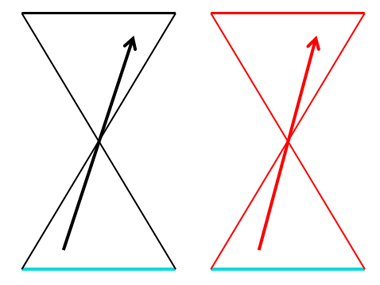

- Equality: On the Web, the user has exactly the same means of communication as the media.

- Memory: On the Web, we have as much memory space as we want.

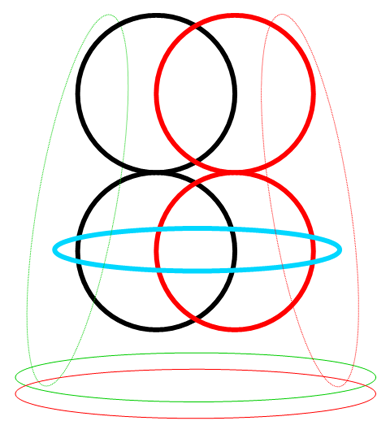

None of the traditional media has any memory of what consumers do with it. Suddenly we can remember all our content, all the content of our users, all the content of our advertisers and all interactions.

On the Web, every content from the media and from the users can be recorded. There is a lot to say about memory. I will add more later. For now, we only need to note that memory is a new fundamental factor in the relationship between media and users.

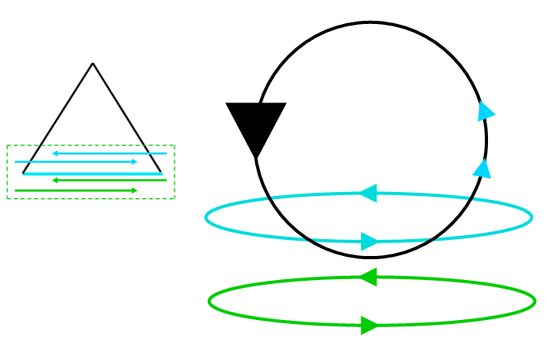

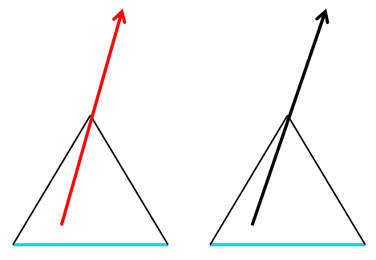

Proximity changes the nature of the exchanges: What happens when you are very close vs very far away.

Origin changes the dynamic of the exchanges: What happens when the media doesn’t move and the user does.

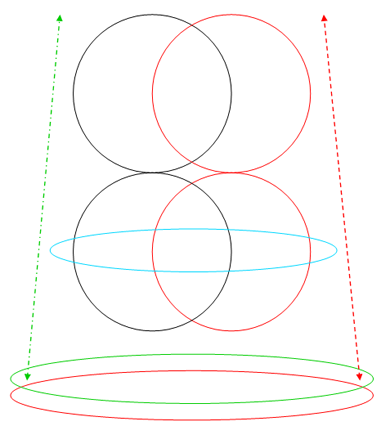

Equality changes the balance of the exchanges: What happens when every exchange is one to one.

Memory changes the nature of the medium, the space where the exchanges takes place, the space available to the media, the context in which all media and all users exist.

The four observations in just four lines:

Proximity: For a user, everything is a second away

Origin: Communication starts from the user

Equality: Any user is equal to whatever is on the screen.

Memory: We have it, we are in it.