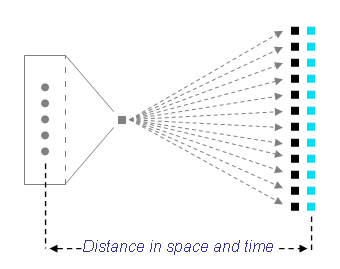

The four parameters of the Welcome System (Proximity, Origin, Equality, Memory) apply everywhere on the Internet. They have consequences for every kind of platform.

Any business on the Web can use features from the Welcome System. And most do, a little here, a little there, without necessarily thinking about it that way: we can recognize, for example, Proximity in applications for eCommerce, Origin in efforts for registering members, Equality in chats for customer service, Memory for storing and displaying archives. Generally, these features are used simply because “it can be done”, not because “it’s a new imperative”.

Once we have identified the Welcome System, we can take full advantage of its properties for maximizing efficiency and profits. We have seen here that the Welcome System is not an extension of the Distance (Media and Marketing) System. It’s a new system, a new territory. This is a disorienting proposition. So, before we plunge head first into a news media project, here are a few pointers for understanding the Welcome territory.

Note: Each of these tips can be the topic of a whole post. What is included here is just a quick overview.

It’s an Open Game

Proximity tells us that, even if users are far away from us, whenever they decide to visit we are only one click away from them. Twitter, Facebook, Google+ and others may seem overwhelming for any business entering the fray but they are not closer our users than we are and never will be. Any site is but a click away from our users.

This makes for a highly competitive environment, but it is an open one. We can start late, or even later, there is no rush: if and when we have a great platform, users surround us and can therefore find us. If we are in it for the long haul, we don’t need Facebook, Google+ nor Twitter or any other service for reaching our users or for building their identity. We can use those services but we don’t really need them. Nobody is too late. Nobody has to play catch up. There is no wall between us and our future users: the Web is wide open.

In this quote from John Battelle, “Facebook” can be replaced with any other social media or network:

It drives me crazy to see major brands using expensive television time to drive consumers to a Facebook program that lives exclusively inside Facebook.

If that same program lives out on the Independent web – your own site, on your own domain, with your own platform – then you own all the data and insights.

My advice: put your taproot into soil that you control, soil that is shared by the millions of other independent voices on the web.

John Battelle

Put Your Taproot Into the Independent Web

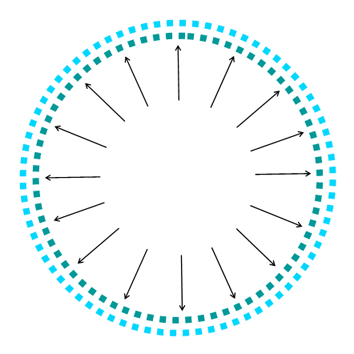

It’s an Open Field

It may sound counter-intuitive, but the Web is almost empty. When memory space expands faster than we can fill it (as we can see for example with YouTube), the available space is nearly infinite. So there is no “real estate” with its “location , location, location” imperative on the Web.

We can set up our tent anywhere, anytime. We have as much room to grow as we want, as big, as ambitious as we want. No other Web site or service is constraining our space or our growth. And wherever we are, whenever we open our doors, we are always smack in the middle of the action, just one click away from our users. It’s an open field. Always.

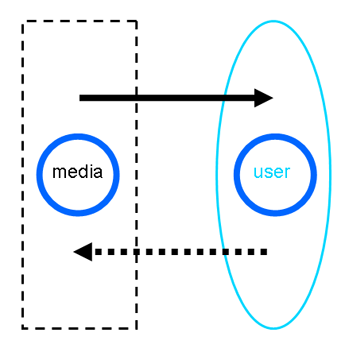

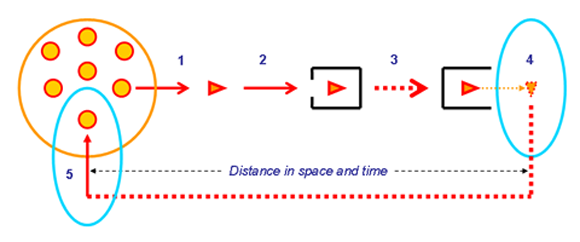

It’s a Stillness Game

Not a pun: Origin is the starting point. Only the readers move. We don’t. For being able to exploit this parameter, we have to get it, internalize it, grok it: we sit down, we stand still, we close our eyes if need be but we don’t move. We don’t send a package. We don’t send anything away. Our website is stuck in a server.

We.

Don’t.

Move.

So this is our home. We can reach people with the Distance game, we can use notifications for calling our members back, but we are where the exchanges take place. This is where we do our business: content exchanges, commercial exchanges. Readers scurry by, on and off again. And our website can’t move to go after them. If we want to do business with them, there is only one question left: what can we do to make them stay here?

Easy: 1- Build a door. 2- Put a big Welcome sign above it. 3- Open the door. Now we need to take into account Equality, Proximity and Memory.

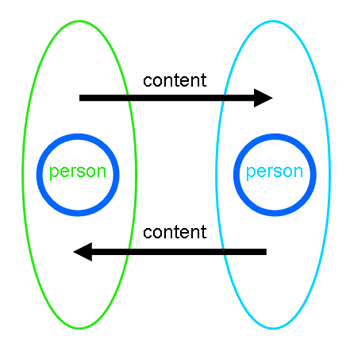

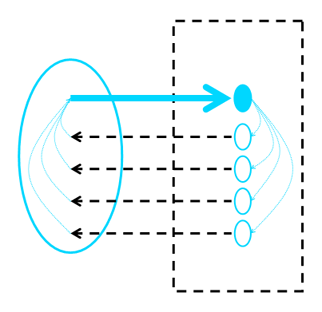

It’s a One-to-One Game

The best use of Equality and Proximity is one-to-one communication. By definition, this is the strangest game changer for mass media and marketing people. But don’t worry: it can be done. You don’t have to exchange personally with all your members. It’s just a place where there are only people: nobody is hiding behind a news media, a brand, a company name, an anonymous title. All that’s needed are people exchanging on a one-to-one basis, like in a forum or a community.

We are used to one-to-one communication in real life. We know how it works. But there is a part of us that excludes these familiar mechanisms from our business on the Web. This is the part that has been shaped by the Distance system. But we have left the Distance system. We are in the Welcome System, where one-to-one rules. This whole process is just about learning how to do business in this new world: one-to-one.

It’s a Community Game

The word “community” is used for all kinds of social groups. It’s not different on the Web, where “community” can have many different meanings. Here, in a Welcome platform, it describes a specific social mechanism with its very own gears and wheels:

– in a Welcome community, members create something together, with at least one main place for common activities;

– a “member” is a registered user whose identity is stable and whose every contribution to the site is recorded and easily accessible to all;

– there are clear guidelines of participation and a system to alert moderators (flags);

– moderators are members of the community.

It’s a One-at-a-Time Game

In a one-to-one context, new members arrive one at a time. It’s not about registering; it’s about participating and becoming a contributing member in a community.

Successful communities put the effort in after the registration process. They fight for every member. They introduce members to others. They ensure members make a contribution on their first visit. They initiate and support interesting events/activities for members. They start discussions and prompt people to respond to them. They create content about what members are doing. They take the time to build genuine relationships with members.

Rich Millington

Focus On The Post-Registration Effort

One at a time is a little anticlimactic and difficult to get in a froth over, but one at a time is how we win and how we lose.

Seth Godin

Preparing for the breakthrough/calamity

It’s a Members Game

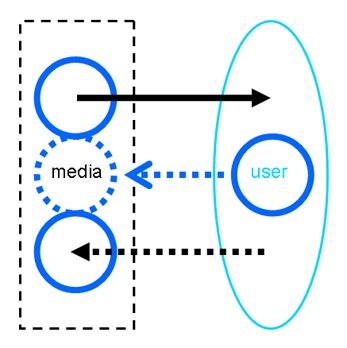

A “user” is a person who happens to pass through any page on our site. A “member” is a registered user who has a stable identity, and whose contributions are recorded and accessible on their personal page on our site. Only members can contribute in a community.

Turn your readers into members. Not visitors, not subscribers; you want members. And then don’t just consult them, but give them tools to consult amongst themselves.

Paul Ford

The Web Is a Customer Service Medium

It’s a Participation Game

Communities don’t care about page views: it’s a place where members do something together. It’s more of a workshop than a theater: there are no spectators, only people working toward a common goal. A Welcome community is about doing and making (active), not about viewing or consuming (passive).

It’s quite simple: members are contributors. There are hundreds of ways – from the smallest to the biggest – of contributing to common goals. But consuming is not one of them. A member is neither a user nor a commenter: a member is a person who cares for our topic and who can contribute to it in a useful and appreciated way.

A member is one of “us”.

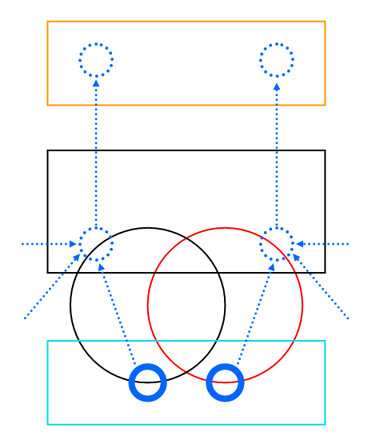

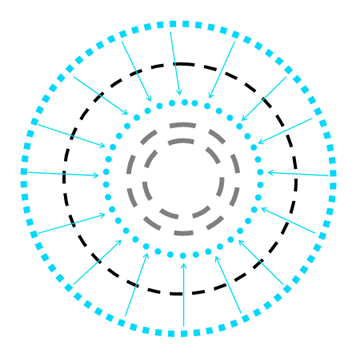

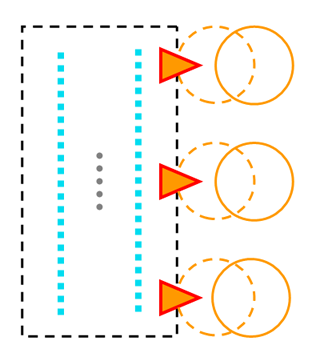

It’s a Non-Media Media Game

If we are creating a private community, it has its own end. The process of becoming a community in the Welcome system is about doing something together. There is no need for another process.

But if part (or all) of the content produced by the community is displayed to the public, it can attract onlookers. So even if the whole process of a community is only about members (insiders) who do something together, they can attract a mass of viewers (outsiders): the content produced by a Welcome community can therefore become mass media.

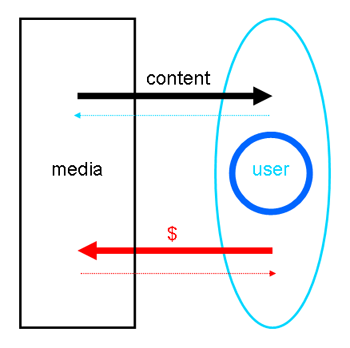

It is important to understand that every step of the way, the community operates in the Welcome system, whereas mass media operates in the Distance system.

Both can happen at the same time and have the same content but the two operations involve totally different mechanisms.

For example, in some communities logged-in members can create content and don’t see ads, outsiders see ads and can’t contribute.

Producing content that becomes mass media is only a side effect of the process of a community, not the community process itself.

So when the content of a community is displayed publicly, only the “side effect” needs to be operated in the Distance system.

The public content can then have all the features of mass media. For revenues: marketing and advertising. For engagement: comments from unregistered users.

The community continues to operate in the Welcome system, with content created by its members.

It’s a Slow Game

A community is made of interpersonal exchanges around a common objective. So it can only grow one person at a time, one new member at a time.

Look at the biggest (non community) social networks like Facebook or Twitter: they took two years just to appear on the radar.

If we try to rush the process, members won’t build an identity, won’t establish relationships, won’t build a reputation and won’t build their home in our home: they won’t come back.

We need a long-term perspective. We need to focus on the lifetime value of members. If you demand short-term results, you build a short-term community. You build a community based upon clicks.

Relationships aren’t built upon clicks. Relationships are built upon meaningful interactions. Relationships are built upon increasing levels of self-disclosure, gradual (gradual!) development of trust and familiarity.

Rich Millington

Member Lifetime Value

It’s an Ever Growing Investment

Every contribution to a community makes it grow: a vote, a comment, a choice in a poll, a piece of information, a picture, a review, a video, a news story, a compliment, a flag, a question, an answer, anything. Each contribution adds a little to the identity of the member, to their sense of belonging to the community, to the exchanges with other members, to the content of the community and to its governance. There is no loss. Ever. Even mistakes are lessons for the member, for the community, for the moderators.

A Welcome community is an ever growing capital.

It’s an Identity Game

In real life, we don’t have to know the legal identity of someone to have a casual information exchange or a commercial exchange with them. Most or the time, if we come to know better the people with whom we have regular casual or commercial exchanges, it is because we remember them.

This is how we build identities in a Welcome platform: by remembering every exchange, every contribution, every transaction. We don’t need a legal identity anymore than in real life. We just need a stable identity, to which we can attach every recorded contribution. Each identity grows with time, each time a member participates.

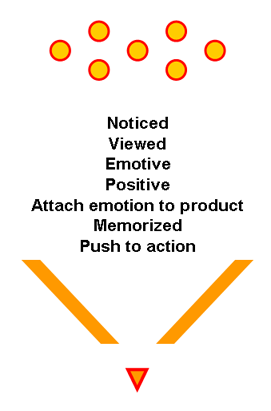

It’s a Trust Game

In the gears and wheels of a Welcome machine, trust is the best lubricant to facilitate any kind of exchange: exchanges of information, news, services, or money.

Trust is made of positive memories of past exchanges.

The more positive exchanges our members have with other members, the more they develop trust between each other.

The more positive exchanges our members have within our community, the more they develop trust toward the community.

To have the best content exchanges, we have to be a trust-generating machine.

To have the best commercial exchanges, we have to be the best trust-generating machine.

It’s a Transaction Game

The Welcome system has a single operating mechanism: exchanges between members.

A conversation is a transaction of information.

An exchange of service, money, or of things is a transaction of value.

There is no difference between the social mechanisms of conversation and of a money transaction between members. Both are one-to-one exchanges between equals.

We just have to provide the platform and the context where people want to exchange information and want to exchange value.

The Urban Metaphor isn’t…

Proximity, Origin and Equality define “A space that doesn’t move where people have one-to-one exchanges”. This definition has a lot in common with what happens in real life in any store. So if we want to understand how a Welcome platform works, we have much more to learn from store builders and managers than from media and marketing people (who operate in the Distance System).

So when we use a urban metaphor for explaining relationships in a Web community, it is not a metaphor: it is the exact representation of what is going on.

There are two main differences between urban life and Web life, though: identity and memory.

In urban life, we have a holistic perception of identity. When meeting face to face with someone, we have a huge bandwidth of communication across all the senses that allows us to absorb a lot of information: height, build, clothing, voice, smell, attitude, tone, stance, rhythm, skin, empathy, smile, gaze, accent etc.

In Web life, even what we call bandwidth is meager compared to urban life. We have almost no real perception. But we have huge advantages: we have memory; we have stable identity; we have an accumulation of information on an identity. And we have identity over as many topics as we care to record, of which any store manager can’t even dream of having in urban life.

It’s a Relationship Game

Equality tells us that users feel equal to whatever is on their screen. So they are in an equal relationship not only with any other user but also with any website.

Relationships are made of exchanges of information and of the memory of these exchanges.

If we want to enter in a stable relationship with our users, we first have to make sure that they feel equal to us in the information exchange. Since we have much more stuff than they have, we have to make sure that they always feel welcome to contribute to the site.

And since we are the ones that need to have this relationship the most (users have countless other choices), we have to host all the events of these exchanges: we have to host for every member the memory of all their contributions, all their exchanges with other members and with the site. And these recorded memories have to be easily accessible to every member so they can see easily and find the history (and the strength) of their relationships on our site.

It’s a Memory Game

Memory allows the building of identity.

Memory allows the building of relationships.

Memory allows the building of trust.

Memory space allows us to host exchanges between our members, to record these exchanges, to host the identity of our members, their relationships and maintain their trust.

It’s a Welcoming Game

In the end, in a Welcome community, we want people to like our place, to feel secure in it and to settle among us to have exchanges with other people.

Our first job is not to send them anything but to welcome them, one by one, to give them their own place and to help them to have meaningful exchanges with others.

As much as traditional communication is about sending packages, a Welcome platform is about creating an available space for people to settle in.

One of those days, we are going to have a conference for platform builders where all the speakers will be from the hospitality business: hotel and restaurant builders, architects, designers and managers.

Your comments and questions are very welcome.